Neuerscheinungen

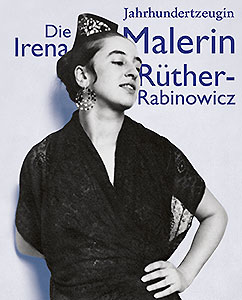

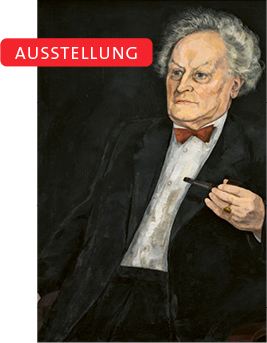

Die Malerin Irena Rüther-Rabinowicz

Hg. Städtische Galerie Dresden – Kunstsammlung; Johannes Schmidt

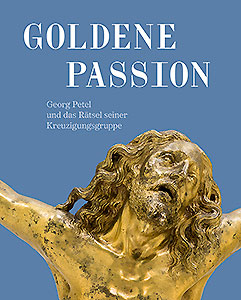

Georg Petel und das Rätsel seiner Kreuzigungsgruppe

Hg. Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, München; Frank Matthias Kammel

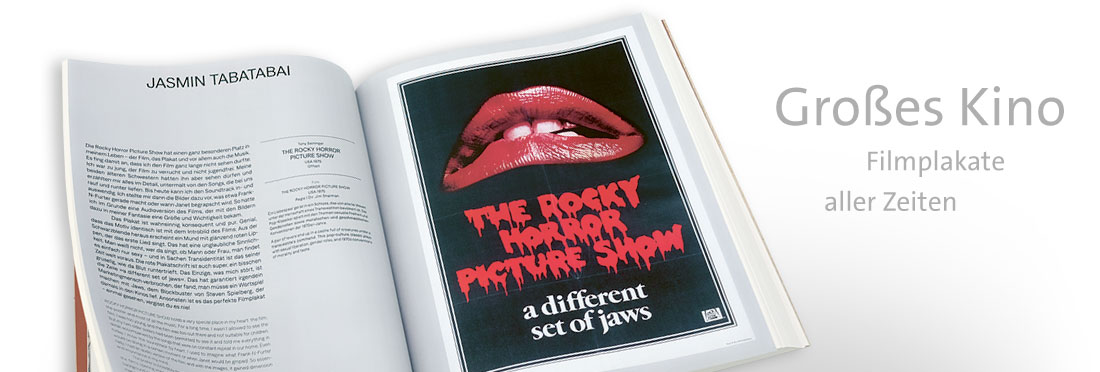

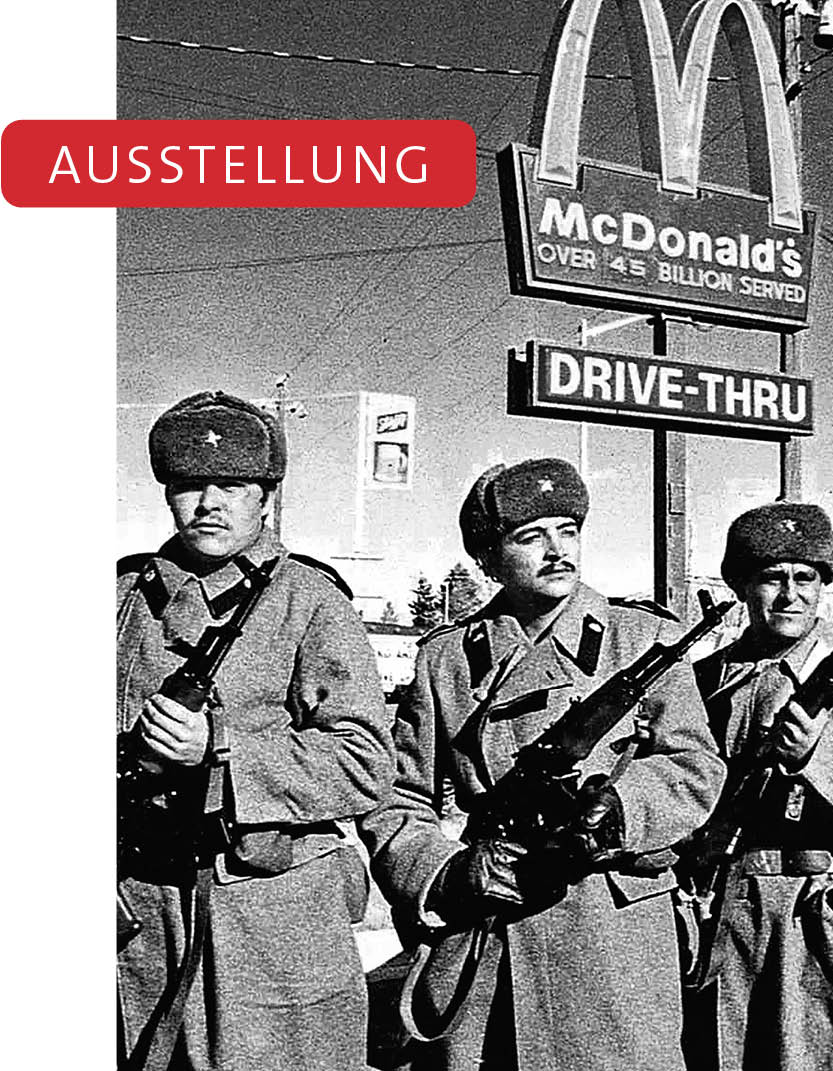

1895 bis Heute

Hg. Weltkulturerbe Völklinger Hütte; Ralf Beil; Rainer Rother

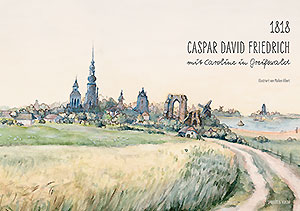

Hg. Pommersches Landesmuseum Greifswald

Fotografieren in der DDR

Hg. Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz, Kunstsammlungen am Theaterplatz; Anja Richter; Johanna Gerling

Aktuelles